This is a Chinese language programme without subtitles.

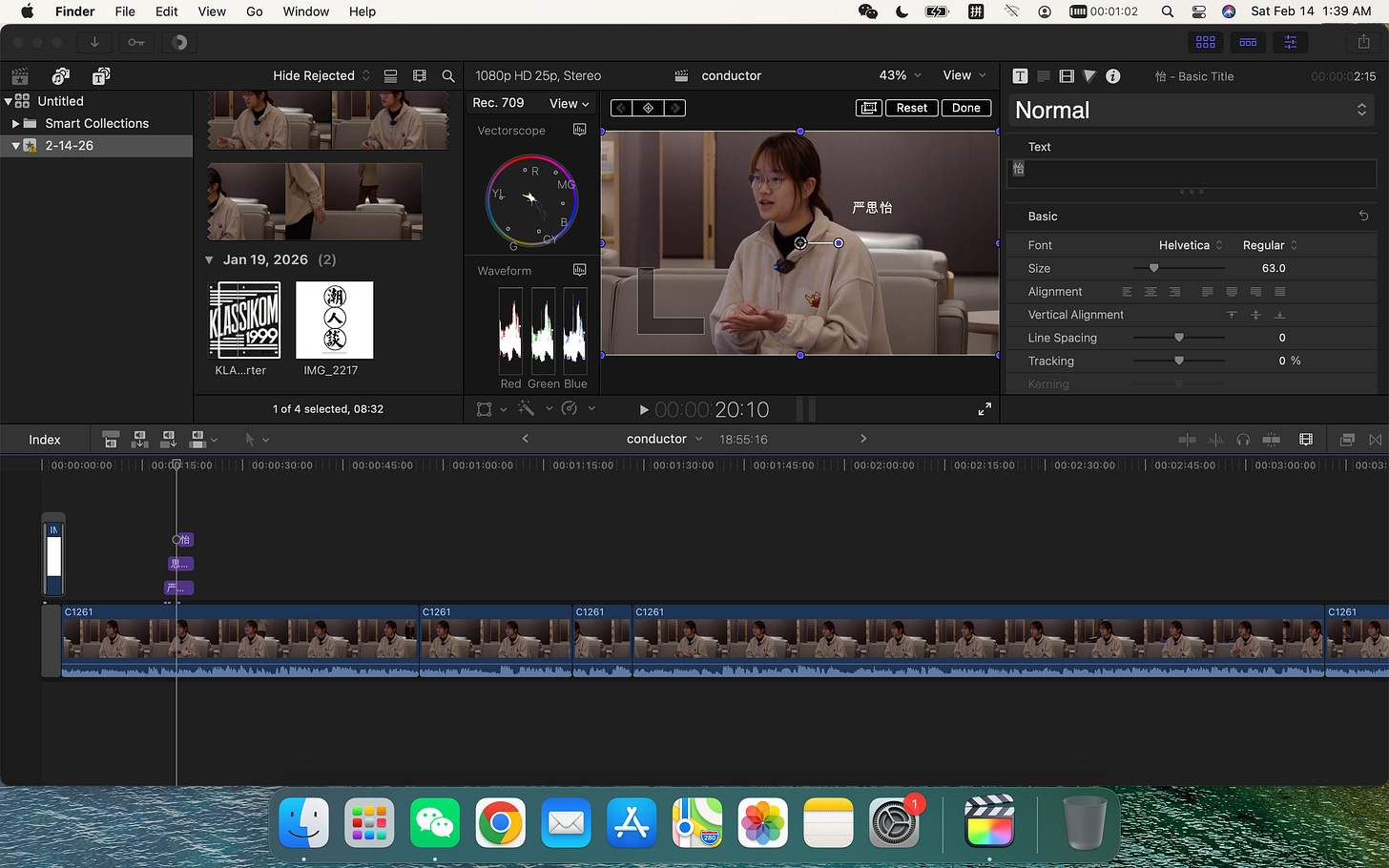

Yan Siyi likes to joke that she became a conductor by accident.

The 20-something musician from Shaxian, a small county in Sanming, Fujian province, did not grow up dreaming of standing before a symphony orchestra. She studied piano in secondary school. During preparations for conservatory entrance exams, she became interested in composition. It was only after a teacher’s assessment and suggestion that she shifted toward conducting — a field she barely understood at the time.

“I just knew it was difficult,” she recalls. “Comprehensive. Demanding.”

What conducting truly meant would reveal itself only later.

Yan completed her undergraduate studies at Xinghai Conservatory of Music and is now pursuing a master’s degree in orchestral conducting at the Shenzhen Conservatory of Music, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. The discipline may sound lofty, even slightly intimidating, but her own path toward it was anything but grand.

Learning to Hear in Three Dimensions

Growing up in a small county town, Yan rarely had the chance to attend live symphonic performances. Her understanding of orchestral sound came largely from videos and classroom instruction. The first time she stood on a podium in front of a full symphony orchestra, she describes the experience as overwhelming.

“The sound came from everywhere,” she says. “It was completely different from rehearsing with two pianos.”

If the piano can present structure and harmony, the orchestra adds color, dimension, and spatial depth. The breathing of the strings, the texture of the woodwinds, the tension of the brass — each reshapes the music’s trajectory. A piano reduction might clarify the score, but it does not teach one how to command an orchestra.

Developing a sense of timbre and sonic architecture became one of her earliest lessons.

She compares reading a full score to reading classical Chinese — densely compressed, highly coded language that must first be understood before it can be translated into living sound. A conductor must grasp the composer’s intent, perceive structural logic, build an overarching conception, and ultimately communicate that vision through rehearsal.

It is translation work in the deepest sense — intellectual, technical, and psychological.

Her passion for conducting grew gradually through study. It is a discipline that demands technical precision, theoretical knowledge, communication skills, and emotional steadiness in equal measure. When a fascination becomes a profession, however, it brings pressure and moments of doubt. There have been times, she admits, when exhaustion led her to question whether she could commit to this path for life.

Yet whenever she reopens a score, the focus returns.

Competition: Preparation, Luck, and Absorption

The inaugural Young Conductors Conference founded by conductor Yongyan Hu marked Yan’s first experience in a major conducting competition. After preliminary selection, masterclasses, and multiple competitive rounds, she advanced to the final five and was awarded the Best Conductor Prize.

She is reluctant to attribute the result solely to personal excellence. The differences among participants were slight, she says; many were outstanding. Success required preparation, but also an element of chance.

Drawing a piece that suited her musical temperament helped. She was assigned a movement from Dvořák — rich in emotional contrast, balancing lyricism with surging momentum — a combination that aligned naturally with her expressive instincts. Yet repertoire alone does not determine outcome.

Equally decisive was her ability to absorb guidance quickly. During the forum, several distinguished mentors offered feedback. The challenge was not simply to listen but to internalize their suggestions and apply adjustments immediately in the next rehearsal. Conducting competitions test far more than musical ideas; they demand time management, adaptability, and collaborative leadership.

Equally valuable was observing her peers. Watching other conductors rehearse revealed both strengths and blind spots. Through comparison, she became aware of her own potential weaknesses — often in small details that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Growth, she discovered, frequently lies in correcting subtleties.

A Woman on the Podium

Conducting has long been a male-dominated profession. Early in her studies, Yan encountered occasional bias — situations in which male students were favored under similar conditions. Yet she does not see this as the defining reality of her experience, nor as a fixed condition.

The industry is changing.

Attributes such as height, presence, or physical stature were once considered advantages on the podium. But in practice, she believes, musical authority depends on professional competence rather than outward appearance.

A conductor stands before a group of highly trained musicians, many with decades of experience. Building a productive working relationship requires clarity of role. A conductor is neither a distant authoritarian nor a passive coordinator. The role is closer to that of a project leader — someone responsible for shaping a shared artistic goal.

The required skills fall into two broad categories. The first includes foundational training: ear training, orchestration, formal analysis, and full-score reading. The second is practical: diagnosing problems in real time, proposing solutions, and communicating them effectively.

Authority, she suggests, is less about dominance than about responsibility and judgment.

Masters and Minimalism

When asked about her idols, Yan does not name a single towering figure. Instead, she is drawn to specific interpretive moments.

One such example is Myung-Whun Chung’s interpretation of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. What impressed her was the economy of gesture. There was no theatrical flourish, no exaggerated display — yet the music flowed with clarity and internal momentum.

“The movements looked simple,” she says, “but inside them was structure and direction.”

For her, this restraint carries profound power. Conducting gestures need not be elaborate; what matters is whether they truly embody the music. The simpler the exterior, the richer the internal intention.

Her mentor, Hu Yongyan, has similarly emphasized that even a seemingly circular hand motion serves to sustain the broader musical line. Mature expression, he teaches, allows all elements to converge naturally rather than fracture under isolated emphasis.

Beyond the Prize

From Shaxian to the professional podium, Yan Siyi’s path contains no dramatic myth. Instead, it reflects steady accumulation.

She does not rush to define her future in grand terms. The championship, she insists, is only a stage of affirmation. The real work continues — between the printed score and the living orchestra.

She may have “stumbled” into conducting, but through rehearsal after rehearsal, page after page of score study, she has found direction. Perhaps precisely because she began without a grand blueprint, she has allowed the practice itself to shape her.

The prize marks a milestone. The larger question — how to become not just a conductor, but a musician of depth and integrity — remains open, unfolding with every new score she lifts to the stand.